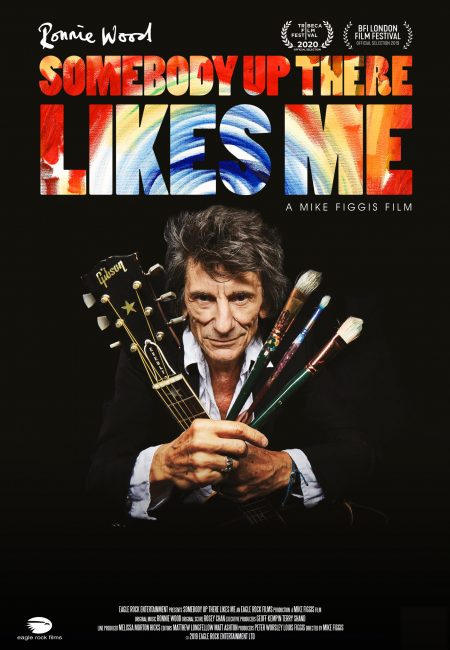

Initially set to make its North American premiere at the 2020 Tribeca Film Festival, “Somebody Up There Likes Me” has been made available for press on Tribeca’s online portal. While the coronavirus had other plans for us to see the film, perhaps at-home viewing makes this delicate portrait of legendary Rolling Stones musician, Ronnie Wood, even more intimate and special.

Helmed by British auteur Mike Figgis, the film delves into Wood’s life as a painter, performer and, well, human. Besides his ongoing and iconic career as a member of the Rolling Stones, we also get to know Wood for his work with The Birds, Jeff Beck, The Barbarians, Rod Stewart, and The Faces.

Known for his work as a writer, director, composer and photographer, Figgis has never not made something that makes you think. In the mainstream, he is best known for his films, “Internal Affairs”, which revived Richard Gere’s career, and “Leaving Las Vegas” which was nominated by the Academy for Best Director, Best Adapted Screenplay and Best Actress and, of course, made Nicolas Cage an Oscar winner for Best Actor.

On Friday, May 1st 2020, NOIAFT founder Taylor Taglianetti had the opportunity to shoot the breeze with the genuine and affable Figgis about his film and the future of filmmaking.

From your narrative work, you seem to show characters exactly as they are. You don’t sugarcoat anything. For a public figure like Ronnie Wood, where do you draw the line?

When I began the documentary, I had some conversations with the production company and I said, “Okay, what are your parameters here?” They didn’t actually say, “You can’t do this,” but they said, “Can you actually just steer a little bit clear of some of the more controversial media headlines stuff?” I said “sure” because I never intended to make an investigative rockumentary. I just thought he was a really interesting character. We didn’t know each other personally at that point so I was totally up for the idea of, “Let’s see where it goes…” I never threw a curveball at him or anything like that. As we got to know each other and we actually got on pretty well, he started opening up. So, there were a couple of sessions where he was very, very frank and because he’s a raconteur, he really got into the storytelling. It was pretty dark so at a certain point when I finished the film and showed it to him for the first time…that’s always an interesting moment in a documentary, I suppose. In a feature film, you show it to a bunch of people and then you try and gauge the audience, but if it’s about a person…he actually sat in a room about one meter away from me. I was actually watching him on the screen, pretty much split 50/50, to see what his response was. Plus, there were a bunch of record executives there and Rolling Stones people all, in a way, checking each other out. Then collectively laughing at some bits, then cautiously laughing at other bits, and then laughing more. So, it was really interesting. I wish I had filmed that actually!

Afterwards, I got not a demand, but a request to maybe take a few things out that Ronnie thought might be hurtful to other people. So I said “sure.” I looked at it and saw it wouldn’t affect anything. As always, you fear with working with a celebrity, they might say, “No, you can’t use any of that.” Suddenly, you don’t have the film that you thought you were making. In this particular instance, it actually didn’t make a difference to this structure so I was happy to do that and they were very, very minor changes. They were cut from a rather humane point of view rather than anything else. Nothing to do with Ronnie in a way from protecting himself, but really protecting other people, family, friends, and so on.

You mentioned that it didn’t affect the structure of the film and you are known for your unique and refreshing ways of telling stories. In the press notes, you mention that the documentary is really a portrait. As an audience member, I would describe it as a breathing portrait. It felt very much like an oral history, of sorts, for posterity. Did you always settle on a structure?

No, I didn’t have a structure actually. The deal was very simple and, in a way, complicated which was: he’s a busy guy…he’s in the Rolling Stones! I was very busy too, so we agreed when we mutually had a day, we would continue and there would be, let’s say, a series of about six conversations. Plus, I put him up in the painting studio with Damien Hirst. Then, there was another really lovely session where we went to this beautiful analog recording studio in London and made some music that was entirely spontaneous. So, I was kind of getting a sense of what we had because it’s very graphic and clear in my mind what we had. Then there’s that thing of which I’m not a fan where you’re shooting two, sometimes three cameras because that’s how they do it. There’s vast storage amounts of interview footage being logged and with an editor that I hadn’t actually given any indication of structure to. I didn’t want to because I told him it would find its own structure when it was done, but then I found that I was really swimming upstream against this log footage which was kind of saying, “Oh, put me in sequence. Let’s do a rockumentary,” and I really don’t want to do that. I wanted the footage to speak to me and say, “No, this is a better way to do it more anecdotally.” So, that was kind of tough initially.

Then what happened was we had asked Mark Ronson to do a collaboration with us on the soundtrack. My idea was to get Ronnie and Mark in a studio together and have Ronnie just jam for a bit and then Mark Ronson put his magic on it and make some sort of R&B soundtrack for the film. It was also key for him as a musician so I liked the idea that it wasn’t a separate thing. Then, Mark Ronson got really busy and I said, “Let’s just do it anyway.” Thankfully, Ronnie just let me run with it. He let me produce the music sessions which was my favorite thing anyway.

He allowed me to boss him around and say, “Okay, just play some riffs. Do this. Here’s a click track.” I put the percussion and bass tracks together. Once we started building the music track, it somehow started to have an organic sense of a shape. Then, I went into a new pair of headlights. Suddenly, it went a lot quicker and then it started to take shape. Once that happens with a film, it starts speaking to you in a certain way: “You should put that there. You should move that. That should go there.” It starts to make sense. It’s tricky because the last few years I’ve edited everything that I’ve shot myself. I love all that. I love, now, the filmmaking process because with digital, you can take your time. You can shoot it and edit it and you retain a kind of overview, so I haven’t really gone back to that system of working with an editor for quite a while. It was a bit of a challenge for me actually, but we got there.

Well, as a musician, do you find that you’re more at ease finding that heartbeat and pace in the editing?

Yes. Ronnie is two things. He’s described himself as a painter and a musician. He’s very collaborative and all of that. Someone like Ronnie Wood, you’d want to do that…I always really like doing art documentaries because if you’re with a dancer or you’re working with a musician, that genre seems to work really well with the documentary. It seems to suggest its own rhythms. You start cutting things in time. That whole section where he talks about joining the Rolling Stones, finally, and then you get Mick Jagger and Keith Richards and Charlie Watts and everybody throwing in their ten cents worth…that had all the potential to be quite traditional. I wouldn’t describe it as dull because it’s quite interesting stuff, but you’re kind of like, “Oh, we’re into one of those montages, are we?” So, the music track there was just fabulous. It did allow you to be, not severe, but pretty sharp on the editing there. “What’s the main points I want to make there?” And boom. Cut it in time to the music and then flip between all those characters because then finally, you have all of the Rolling Stones talking about Ronnie. I think that was also a turning point and that came about once we’d done the music session and that’s a very important part of the film.

Is there ever a point when you’re composing the music that you’re worried you might be overwhelming the music that Ronnie’s playing or even the amazing music from the archival footage that you included? Do you ever get a feeling of, “Oh my gosh, I have to step back and actually really see where and if this fits?”

Yeah, particularly something like this. You do try. There’s only two bits where, let’s say, we go out of the Rolling Stones vibe or Ronnie vibe because when he’s playing acoustic guitar, there’s the soundtrack. It’s great. Anything that’s him playing music, in a way, that’s narrative rather than score. The bits where I thought score might work was where I used a little bit of composition under the dark section where he talks about going to the edge and it being too much and we’re leading up to him going to final rehab. That, I felt, was justified because he was telling a dark story. The other bits with the painting where Rosey Chan did the score…that kind of slightly, almost impressionistic, piano seemed to say that this is another world he inhabits which has nothing to do with rock and roll. A completely different kind of aesthetic. I wanted people to see that he wasn’t a rock and roll painter. I mean loads of celebrities paint and draw, a bit of oil and canvas and all of that, but he’s actually really good. His line drawing is actually really beautiful and quite Matisse-like sometimes. I just loved watching him working. His physicality took on a completely different demeanor from his stage presence and he’s dead serious. The film deserves to frame this in a very serious way. That would be the only time I thought, “Yeah, score would work there.” I think that’s it in the film. As far as I know, those are the only bits that take you out of Rolling Stones territory.

Well, when you get such beautiful footage like that, how do you know when to show those interviews and those experimental conversations where you have Ronnie picking cards and using it as sort of a springboard to speak about certain things, as opposed to the vast amounts of archival footage you can choose from? It had to have been the toughest job choosing what to select and where to put it.

I guess that’s how the many years of filmmaking does become useful and pay off because at a certain point, you accumulate knowledge. You’re also trying to protect your instincts of when to cut. I’m just editing something now and I hadn’t looked at it for a month and I’ve just slashed 30% of the footage. All very lovely and everything but it’s what I would say to students. Ask yourself the question: has the story moved on in a good way by including that clip? If the answer is: “It’s very pretty but not really,” then it can’t really be there because film is very unforgiving.

I’m not a huge fan of the three-hour documentary. This ended up being 80 minutes or something. I thought it was a good length and obviously, as you say, there’s so much archive footage so you have to be really judgmental about what is a little diamond that we can put in here. I love the stuff of him with his own band and him as a frontman. I thought that’s really good to show the audience him as the frontman because he’s so confident. He’s a really good singer, quite capable of being the frontman, and yet a part of his personality is that he’s a bit of an ensemble player. He’s very collaborative. He likes playing with and behind other people, too. That’s kind of a way of showing that and it is tricky. Ultimately, time is such a funny thing, isn’t it? You just watch it and say, “Let’s take more of that scene.” There’s always that thing where “Is there a bit in the film where suddenly it’s like a bit slow because I’ve seen it so many times? Do I feel that we could fast forward over this?” So you try to get the film so you don’t have that feeling.

I think documentaries are becoming very, very popular right now. You had mentioned you’re not a big fan of those three hour ones. However, do you feel that with documentaries breaking box-office records and series like Tiger King becoming phenomenons, do you think that the appetite for documentaries has any influence on you when you’re creating? I know that you’re kind of against commercial trends and things like that, but do you have any trends in mind when you are creating something like this?

Sure. I’m also very wary of the facts. I think there’s so much wrong with documentaries now as well because they, in a way, invaded the feature film world as being viable as feature-length. That means that they’re conforming to certain preset lengths in order to conform to box office. They’ve stolen all of the worst tropes of a feature film like overly sentimental score, overly commenting score, and way too much score so there’s never a quiet moment. Even in the most serious documentaries on the BBC, there’s always some throbbing score going on or some pseudo Philip Glass piano to tell you it’s kind of an abstracted sadness or something. So, I kind of got very bored with the way they’re using these very limited devices and I also get the feeling that a lot of their script was written before the documentary was shot, which seems to be counter-documentary.

The whole joy of documentaries is that you go on a journey and you find out something and then you come to a conclusion when you’re done. Most documentaries that I see came to the conclusion and raised the money before they ever shot a frame of video, so I find that they suffer from the same commercial pitfalls as the feature film industry. Having said that, there’s some great stuff out there as well. I mean the truth is there’s a lot of stuff. A lot of people are shooting now, the biggest challenge in a way. Lockdown is like a dream come true for Netflix and for everybody else, right? [Joking] What else are you going to do but watch Netflix? It’s, in a way, wrong to conflate anything from this period because it’s such an artificial period. The appetite is so artificial compared to what’s going to happen when we start to become social again, I hope.

To that point, with the pandemic, people are really having to rethink the structure and content of films. Do you think that the industry will change permanently for certain things that we’re experiencing now? I know that some people have actually mentioned your film “Timecode” in a number of articles. Someone’s bound to make another version of it through Zoom!

Yeah, I know…funny, isn’t it? It’s just a phenomenon to throw something up like that. But, it’s such a good question. It’s such a good debate right now. I’ve been talking to producers, filmmakers, actors, and everyone is obviously really worried. There’s a very good article in the LA Times about the future of studio film production. It answered a lot of questions. I’ve been talking to my agent saying a very highly placed film producer in England had said that he foresaw that there wouldn’t be any major film production for quite a long time because of insurance. No one is going to get insurance. It’s just too risky. We don’t know about the second wave. We don’t know about re-infection. We don’t know about anything. So, until scientifically certain things are clarified, there’s going to be too much economic fear. In the LA Times article, they were talking about reducing film crews from 180 units to units of 70. Disinfecting the sets first and all of this stuff, but then think about actors. Who’s going to want to kiss anybody or have a close contact fight with someone or a simulated sex scene? I think it’ll take a while for us to stop being phobic about contact, number one. And with that, there comes…do we want to see those kinds of stories? Are we going to an era where we’ll be looking at a much more isolated humanity as a trope for storytelling? I think that may be the case out of a combination of necessity because if you go to a studio and say, “I want to make a film about one man on a desert island,” they go, “Perfect! That’s the film we want to make.” And…I’m Mike Figgis and I can shoot it with basically three people and they can be sixty meters a part at any given time. I’m about to do an opera in a lockdown with just one singer. I’m going to make a film. Immediately, I think, technically, how do I do that? I figure out a way to do it. It can work but it can work because it’s one person and because I don’t like working with big crews anyway. So, in a way, it’s right up my street. It’s Timecode again so maybe my time has come back!

I think so, ha! Besides the opera, is there anything else you’re working on?

Yes, a couple of features but they’ve been around for a couple of years. They’re in the financing stage. I’m intrigued to see what will happen with them because that’s the same boat as everybody else. They’re regular feature films with several people, many people in the scenes, and a crew. Not 180 people, but with at least 30 or 40 people, a standard crew.

I will be amazed. We were looking at the autumn. I can’t see that happening so there’s that. Maybe another documentary again set in Italy where I can be very light handed with my crew and everything. Already, I’m thinking technically about how to shoot that in a safe way for both the subject and certainly for the crew. I just started thinking about it and I find it quite stimulating. Adapting to situations has always been quite intriguing to me. Usually, it was like you thought you were going to get $10 million and only got $2 million so that was like retrograde adapting.

But adapting this way is like, here’s the circumstance; let’s find a way to continue being creative. Let’s face it. I said this in 2000. The equipment now exists. You can buy a 4K SLR camera for $1,500 with really good sound recording equipment. The appetite for documentary or feature is there and the audience doesn’t really care who shot it and how they shot it. If the story is good, they’ll watch it. Truth is, they’re going to watch it on something like an iPad or a computer, probably. Or in the case of Quibi, they’re going to watch it on an iPhone. I don’t know. We are technically perfectly set up to continue working and adapting very quickly to this situation, so to answer your previous question, I think that’s what’s going to happen. That will forever hone a whole new generation of filmmakers who have adapted quickly or have an economic strategy, a good dollar brain.

When you think about a service like Quibi where the content is short-form, I think we might be getting more of that for the sake of storytelling. Perhaps they’re not doing as well as expected, but still, it’s easier to make something that’s short, but can narratively still be fulfilling.

It’s interesting with Quibi, isn’t it? They were set up to be almost behaving like a studio so they were throwing huge budgets for projects. They wanted them to look like feature films and have all of the value of those things. They wanted them to look expensive. They also wanted them to add up to a big thing but then in bite size, 10 minute pieces. They’re going to have to literally pivot and change their strategy because they are in a sense, market-wise, in a good place with the idea. Just their way of doing the idea is almost overnight obsolete.

That’s all the questions I have. Thank you so much for your time. It’s such a pleasure. I’m quarantined with my family and we binged some of your films before this so you’ve kept us quite entertained.

And everyone is okay?

Everyone’s good. Yeah. Well, we’ve got Netflix so how could we not be?

Check out some Korean drama.

Any recommendations?

K-Dramas…I’m convinced are much better than the American English language stuff. I would give you three. They’re quite long. Sky Castle is unbelievably good. Great cast. I think an American network bought the rights and is going to do an American version. Secret Affair is magnificent. Something in the Rain is very, very good. They’re all about 22 episodes long so it’s perfect lockdown stuff and quite addictive. Obviously, all subtitled but really, really good.

Aren’t you working on a series of Korean short films?

I’m writing a K-Drama now, yeah! So, I’ve been five times to South Korea in the last eighteen months and I’m supposed to be there now. Of course, that didn’t happen. I partnered up with a young Korean female writer and also a production company to produce. Originally, we were going to do three short films but now we’ve extended that into a K-Drama about the #MeToo movement in Korea.

Mike’s viewing suggestions will keep us busy in the meantime but, of course, we’ll anxiously be awaiting to watch Figgis’ next venture post-quarantine.

This interview has been edited and condensed for clarity.

More on Somebody Up There Likes Me: www.ronniewoodmovie.com

More on Mike Figgis: http://www.mikefiggis.co.uk/

Loved “The Loss of Sexual Innocence.” As a Rolling Stones fan, have to see this. Cool that he might be making a film in Italy. I think he’s made a couple of other films there. I also know he directed an episode of the Sopranos. Loved this.